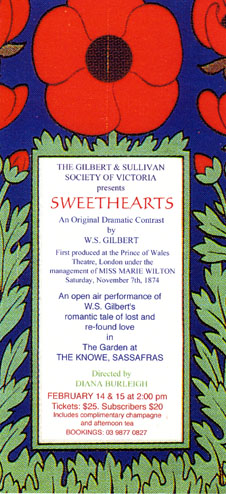

Sweethearts

|

2004 |

DIRECTORS | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| CREW | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Production Manager - Trevor Dawson | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stage Manager - John Larcombe | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Photography - Brian Taylor | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ticket Secretary - Sue Younger | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catering - Brian Taylor and Robert Ray | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Helpers - Janine Evans and Janice Donnelly | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reflections on Sweethearts by Jamie Moffat There is a popular notion that WS Gilbert’s non-Savoy works hold up badly. And it is true that they have had an even harder time than Sullivan’s ‘serious’ music in finding a popular niche. One might make exceptions for The Bab Ballads, which have remained in print almost constantly since their initial appearance, and for Engaged which has even had a West End revival in recent years. But even here there are serious qualifications to be voiced about their durability. The Bab Ballads, it could be argued, are most interesting for representing the Savoy libretti in embryonic form. On their own terms they have notably less appeal. Likewise Engaged bears more than a passing family resemblance to the Savoy Operas. From this slight evidence it would be easy to deduce that Gilbert was a writer of wit, but limited scope. He was, in every sense of the term, a ‘popular’ writer, meaning that he catered to the immediate demands of his audience and looked no further. His many plays therefore have a footnote in the history of the theatre, but his fame does not seem matched by durability or inspiration. Its an argument that could have been made more readily on February 13 than two days later. In the interim period the Gilbert and Sullivan Society’s production of Gilbert’s Sweethearts gave an alternative view of the author’s skills. The results may not have been revelatory, but they were certainly insightful, and easily vindicated Gilbert as more than a writer of popular trash. Sweethearts was in fact one of Gilbert’s greatest successes. He was inclined to think of it as his masterpiece, even though it was obvious well before his death that posterity was going to have other ideas. The play follows his preferred two act form. In Act One we have two young lovers hedge their way around an awkward courtship. He is about to be shipped off to India and longs for some commitment, and she seems to have no idea what she wants. In Act Two, they are reunited thirty years on. Now the situations are reversed. The flighty young woman has grown and mellowed into a perceptive and feeling woman. And her suitor reveals himself the shallow party, insensitive and slightly heartless. For all that, it is an optimistic play and we are left with the suggestion of the romance finally blossoming. On paper it looks like slight material, and its true that Gilbert does not explore his theme with any great depth. But that lightness proves one of its great assets. These are small people. Their passions are shy and withdrawn, dominated by taste and decorum as Victorian Society dictates. But there is a great deal lurking beneath the surface. Gilbert sees no need to spell this out to the audience. Possibly he assumed that they were on the same wave length anyway, but I prefer to think that Sweethearts brings out a restraint with which he is seldom credited. There are other points of interest. Its an early example of the Gilbert using a contrast of setting between two acts to make a strong visual impact. It’s a device that Gilbert would use again most effectively in Ruddigore, The Gondoliers, Utopia Limited and The Grand Duke. He makes a subtle use of it in Sweethearts, the metaphor of a sapling that grows into a tree being particularly strong. Much is made of the protagonists’ changed appearances. It’s a potentially cruel notion, but handled with great sensitivity. Sweethearts also makes nonsense of the frequently made claim that Gilbert had a vendetta against women, and middle aged women in particular. For it is the heroine and not the hero who proves the deeper of the two, and it is made clear that this is considered typical. It is a play that requires some consideration in performance, and it was lucky to have that in the Gilbert and Sullivan Society’s production. Diana Burleigh directed with obvious affection, and this translated into the performances. Above all, it was handled without the condescension that could easily have sunk the whole enterprise. Its unlikely that Sweethearts will ever regain its place in the sun, but it certainly does not deserve oblivion. Its successful revival makes one wonder what else may be lurking in Gilbert’s canon. Therein lies another challenge for the Gilbert and Sullivan Society of Victoria. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||